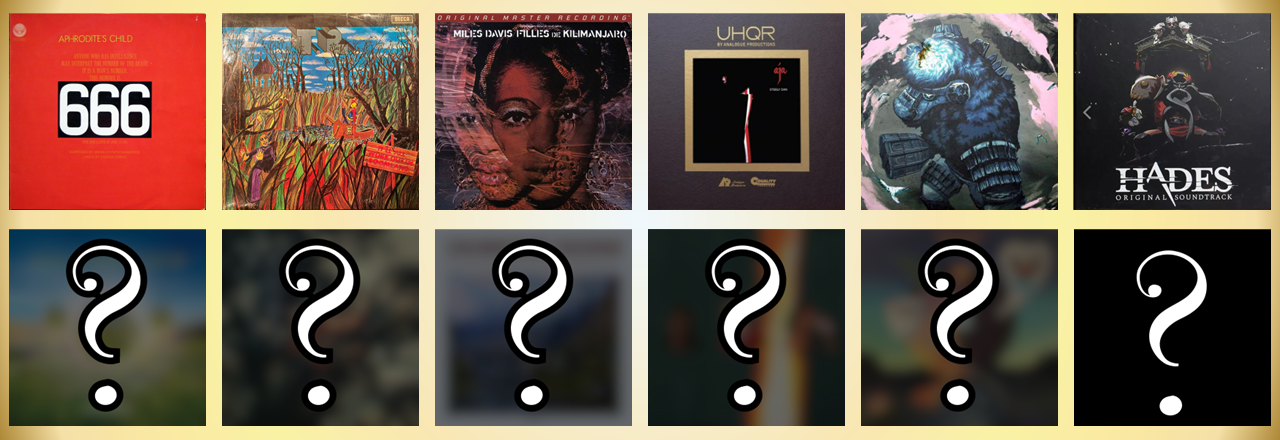

The 2024 12 - Part 3: S-Tier Soundtracks

In 2023 I bought about 175 records. Come 2024, with storage space tight, a growing one-year-old, and a cross-country move on the horizon, a radical shift was in order. This is the third in a series of posts about my “2024 12”, the only twelve records I permitted myself to buy this year in radical departure from my excesses of 2023.

Today’s entries are among the most epic and evocative as it gets in the world of video games, and that’s saying a lot! As a lifelong gamer who works in the gaming industry, video game soundtracks are always going to have big pull on me. But they tend to be costly and the music often just doesn’t land when decontextualized from the artful graphics and sweaty boss battles they are meant to accompany. As a result, these two albums netted me just my thirteenth gaming LP in contrast to my roughly sixty film and TV soundtracks.

Gaming Soundtracks For Everyone

Shadow Of The Colossus: Original Soundtrack by Kow Otani (2005). It’s 2005, the Playstation 2 has sold nearly 100 million units as it enters its final year before the introduction of the Playstation 3. An explosion has unfolded - the world of gaming has drastically expanded, accelarating its transformation from niche hobby to cultural bedrock. This was greatly the result of the innovation seen during this Playstation 2 / XBox 1 / Gamecube era. The game titles from this console generation were a treasure trove, brilliant in quality and wild in variety - and they almost universally had brilliant soundtracks to match. The specialness of this time was stamped by a combination of marquee titles with mainstream appeal and more artistically minded passion projects. Some of the mainstream blockbuster games defining this era were the high octane Halo: Combat Evolved and Halo 2, the debaucherous Grand Theft Auto 3, the gritty Resident Evil 4, the sweeping epic of Final Fantasy X.

On the passion project side were the likes of Team Ico’s Shadow Of The Colossus, an ambitious gamble driven by visionary Fumito Ueda. Colossus began development on the heels of his critically acclaimed but commercially unsuccessful Ico in 2001. Inspired by a combination of classic monster movies (the likes of Godzilla) and the contemporary fascination with violence seen in games like Grand Theft Auto, Ueda wanted Colossus to play on the idea of “cruelty as a means of expression.” His approach however, was more abstract and fantastical as opposed to realistic. The game’s conceit is that the player seeks to revive his deceased lover using the power of an epic temple - but to harness the temple’s power he must find and kill sixteen Colossi, titanic beasts that must be outwit and scaled before the player can begin to exploit their hidden weaknesses. In the game, each Colossus is a unique puzzle all to its own, and the journeys taken to find each one present a uniquely meditative and reflective experience in the otherwise fast-paced, visceral, and cognitively taxing world of gaming. [SPOILER ALERT] For its finale, the game reveals that the player’s quest to massacre these foes was a trick all along, a ploy to unleash a Luciferian demon on Earth. The player is left to contemplate their decision to enact violence, their obedience to authority (the authority of the game), and more - strong themes in its immediately post-9/11 world. [END SPOILERS]

The violence and cruelty in Colossus comes not from gritty realism but from the game’s barren, serene, and awesome vastness contrasting powerfully against the horrific power of its Colossi and the brutality needed to fell them. Another powerful contrast is that the player controls a gaunt, pale, androgynous young male whose appearance fails to project malevolence or physical intimidation. Finally, while the Colossi look like monsters which we stigmatize as evil, the game ultimately frames them as peaceful and precious parts of a gorgeous natural world. Do not judge a book by its cover, the art seems to say.

All of this is powerfully evoked in the game’s brilliant soundtrack: The mysticism of the world, the terror of confronting the Colossi, the pride and shock in moments of victory, the darkness of death, the shimmering hope of resurrection, the regret of misdirected malice. The tracks include contemplative choral arrangements, delicate piano work, stirring strings, sacrosanct flute play, and thundering orchestration. Almost haunted by their beauty, I’ve come back to these tracks many times over the years. So although I had to pay quite the premium to buy this out of print LP second hand (roughly $100, 2.5x its MSRP), it feels special and a well worthy inclusion as one of my twelve purchases this year. One bit of negative snobbery: I think the album’s artwork was well intentioned but ultimately does not live up to the legacy of the game’s beautiful artistic direction. While the game’s graphics have aged and would not read well for album art, the commissioned works undersell the grandeur and weight of the game’s world and the experience playing it.

Hades: Original Soundrack by Darren Korb (2020). Titles like Shadow Of The Colossus were important for paving the way for the next major area of growth for gaming: the rise of Indie games. With the democratization of software development tools, and the opening of digital sales spaces on consoles (XBox Live, The Playstation Store) and especially PC (Steam), in the years following Shadow’s release it became increasingly easier for small teams to develop games and get them to consumers. The mass proliferation of games like Super Meat Boy, Braid, and Journey showed that there was a huge market for games with a small scope, obsessively perfected execution, and lean teams making something deep from the heart.

Released in 2011, Bastion announced Supergiant Games to the world, a studio of just roughly 25 people which has become the pre-eminent indie game maker. From day one, the studio put audio design and composition shoulder-to-shoulder with game design and aesthetics. Indeed, it seems impossible to imagine any of their four titles without the wizardry of their audio director and in-house composer Darren Korb. Impressivley, just as each Supergiant title has its own visual aesthetic and style of gameplay, so too Darren has flexed different genres and instruments to match the experience. Bastion’s outlaw fantasy got “acoustic frontier trip hop”, Transistor’s sci-fi neo noir got “old-world electronic post-rock”, and Pyre’s high fantasy got lounge-y gothic folk.

Hades got “Mediterranean Halloween Prog Rock” - heavy, twisty, creepy, and brooding. A brilliant bit of Greek Mythology fan fiction, the game concerns Zagreus - son of the god of the Underworld, Hades - who will do whatever it takes to escape the land of the undead to reunite with his mother Persophene on Earth. For an immortal god like Zagreus, death is just another beginning, and for the sake of the game, just another opportunity for Zagreus to improve upon his capabilities. Death after death Zagreus gets faster and stronger, hitting harder and weilding increasingly more epic weapons. In his trials, he gets imbued with “Boons” - powers handed down from gods like Zeus and Artemis - making Zagreus capable of devastating attacks as he takes on the swarms of undead in his path.

Like the gameplay, the music is fast and frenetic, and like Zagreus’s dichotomous ability to smite with devastation and evade with tremendous agility, these tracks are also weighty but somehow light. Korb also convincingly contrives beautiful ballads sung by Orpheus and Eurydice (mythologized for their heartbreaking artistry and fatal curiosity respectively) and perfectly dials up the intensity for the game’s white knuckle boss fights. ('The King And The Bull’ is the track that triggers me the most, as it plays during my most feared boss encounter.) The album’s intricate and beautifully layered compositions also magnificently capture the domains of the Underworld which Zagreus must traverse: the gloomy green Tartarus gets spooky synths, the molten hot Asphodel gets thundering drums, and the intoxicating incandescence of Elysium gets elegant acoustic guitars and wispy arpeggios.

Bringing it all home, the packaging on this 4 LP box set nails the assignment. The cover portrays Hades himself in a matter as imposing as he is to face in-game as its final boss. The sleeves feature some of the game’s biggest personalities depicted beautifully as juxtaposed duos. The labels for each side are the game’s icons for the Boons the player chooses from in the game, a central part of the game’s iconography. Finally, my variant of choice was “Clear, Black Smoke” which just looks badass. I bought my copy directly from iam8bit, very grateful they still had them in stock!

The gods of Hades and their Boons

We’re Halfway There

That’s half this year’s albums already! Next up are two albums showing my love for the delicate brilliance of Pink Floyd’s guitar god David Gilmour.